Presentation for the Center for Adivasi Research and Development

April 27, 2023

by Ernest Lowe

Welcome Home! for CARDv4_cmpr

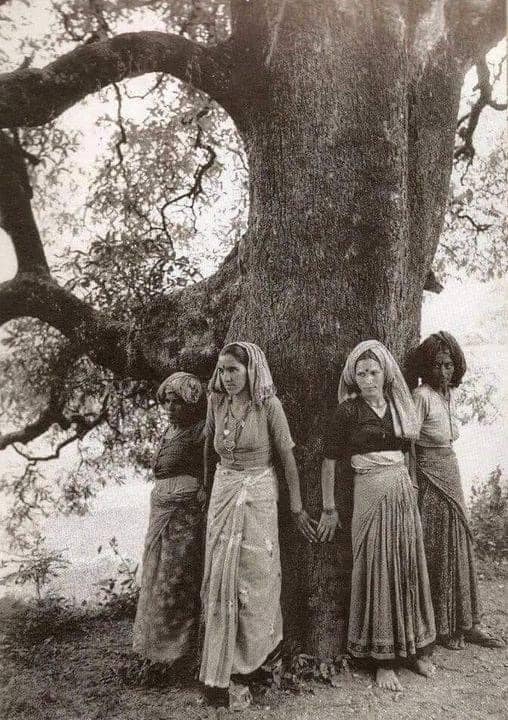

The Tree Saviors of Chipko Andolan

The Tree Saviors of Chipko Andolan Australian Aborigine Dreamtime Painting

Australian Aborigine Dreamtime Painting

Presentation for the Center for Adivasi Research and Development

April 27, 2023

by Ernest Lowe

Welcome Home! for CARDv4_cmpr

The Tree Saviors of Chipko Andolan

The Tree Saviors of Chipko Andolan Australian Aborigine Dreamtime Painting

Australian Aborigine Dreamtime Painting

I find my Dad’s stooped forward posture here

and my Mom’s tightly accounting lips as well.

Their every gesture and tone of voice

every feeling and judgment and way of seeing

all of it in my rulebook for betraying the magic

that’s right here in the splashing of soapy water.

But this boat-person Vietnamese Monk goes on to tell us

how the store room contains all of our interconnections

every star-born atom flowing through us,

letting us off the hook of ever being a separate self.

2019

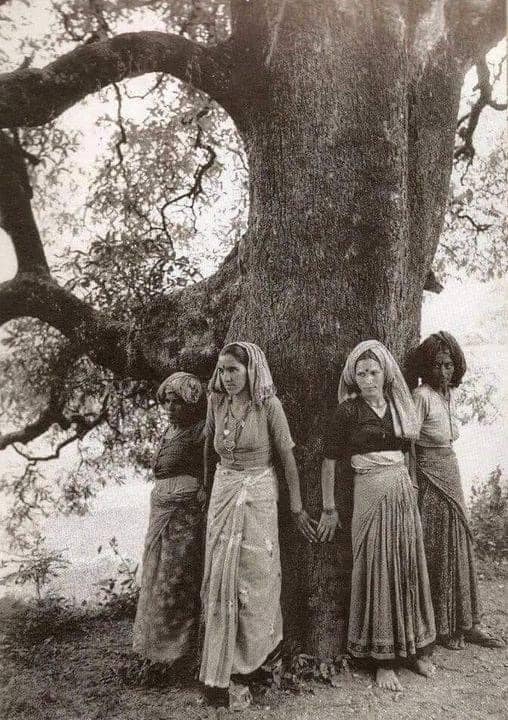

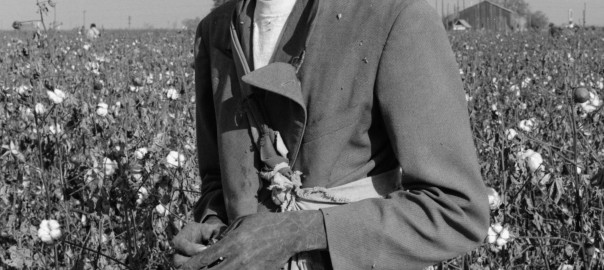

They came from Arkansas, Oklahoma, Texas . . . put down new roots in settlements like Lanare, Fairmead, South Dos Palos, or Teviston . . . camps such as Harris Tractor Farm or Cadillac Jack’s Camp . . . neighborhoods in Stockton, Hanford, and other Valley towns. They were the Black Migrants, moving from rural to rural settings, a little known part of the Great Migration out of the Jim Crow south.

Some were recruited by cotton growers like J. G. Boswell. Others traveled west on their own initiative, fulfilling a powerful ambition to succeed, along with hope to escape the bitter racism they’d come up under.

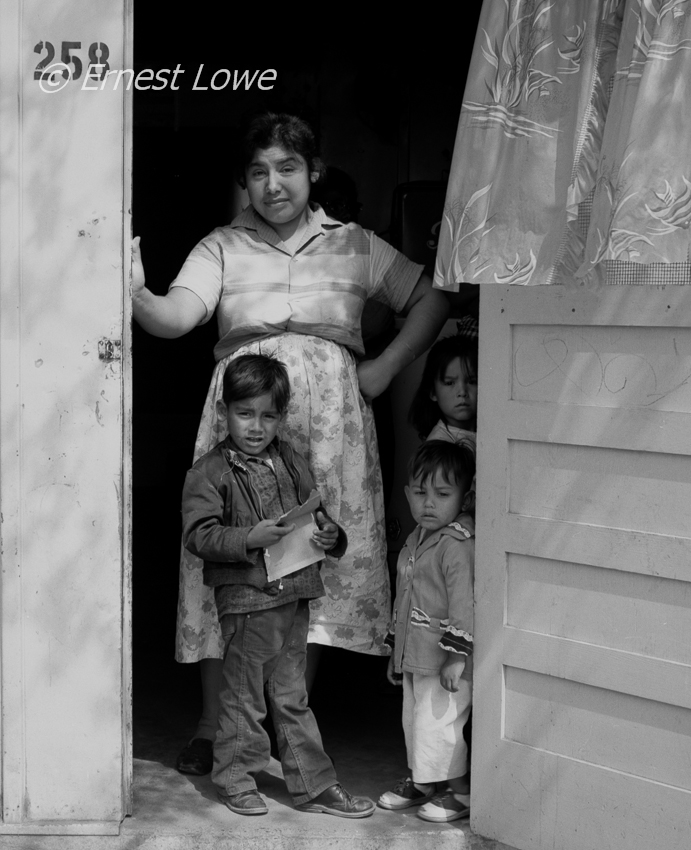

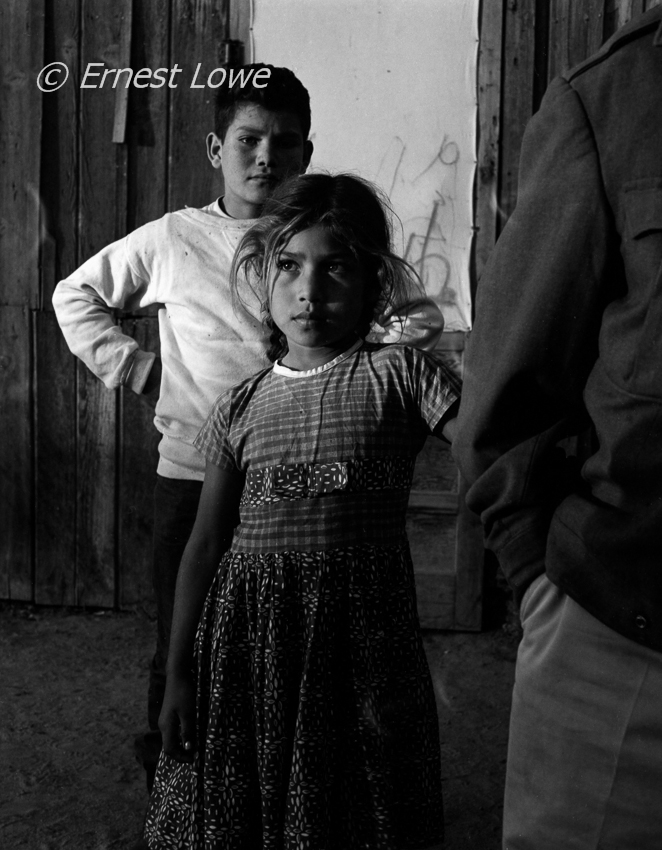

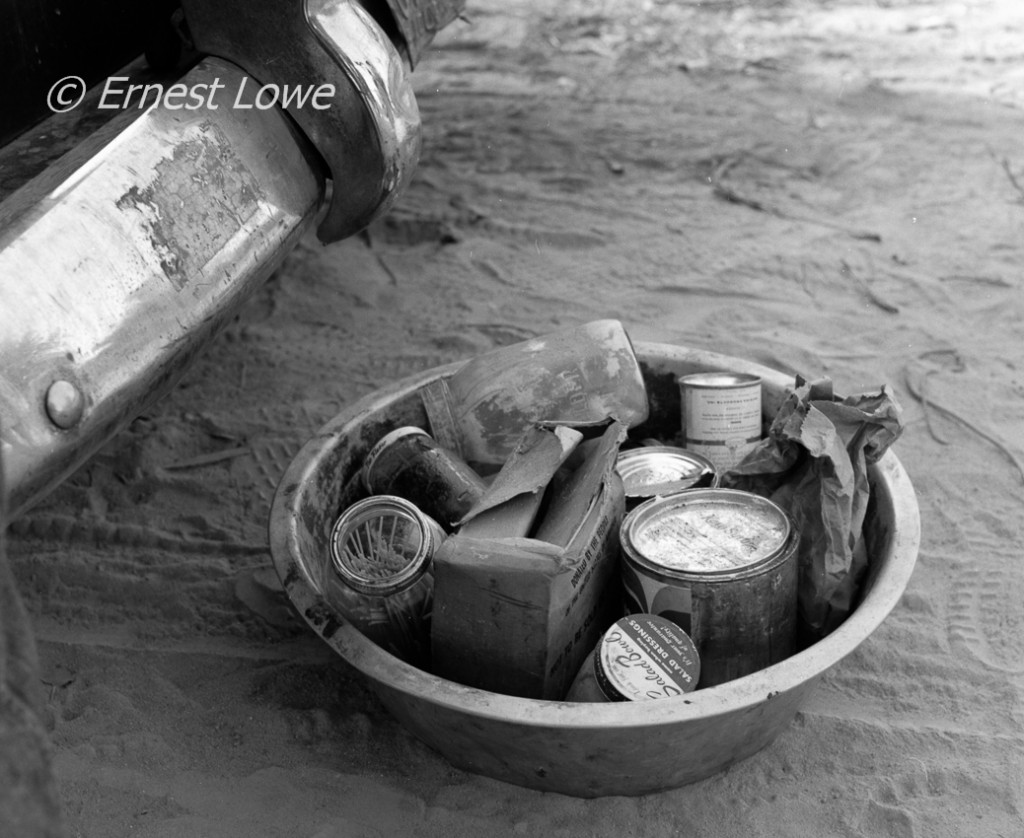

From 1960 to 1966 I photographed them in the Central Valley’s onion and cotton fields, in their unknown settlements, in their tarpaper shacks and trailers. I recorded their stories so the world could hear their voices.

I was a freelance activist documentarian, never pretending to objectivity. I’d walk up to people in a camp or field and say, “I hear you folks are getting a raw deal. I’d like to take your pictures and talk with you so people back in the city can do something about it.” They seldom turned me down.

Although my work documented scenes of dire poverty and backbreaking work, I was also committed to showing the dignity and humanity of these hard working migrants. I saw their strong families and sense of community, even the joy of turning an old rope and tree into a playground for the kids.

Unfortunately the people I met also told stories of how Jim Crow had migrated to the Valley with them: sundown laws, race riots after football games, threats of lynchings. Mothers and fathers told their children, “Just walk on by. Don’t stoop to their level.”

Black Migrants also faced another challenge: by 1961 when I photographed workers picking cotton by hand in a field near Pixley, agro-engineers had developed mechanical cotton pickers that virtually eliminated the need for handpicking by the families I was photographing.

When I returned to Dos Palos and Teviston in 2015 I found many of the folks I’d photographed in the 60’s living successful lives. The children in my 60s photos had succeeded in escaping farm work for jobs in service, hospitality, and government. Their parents’ determination, powerful work ethic, and love had paid off.

Ernest Lowe

Black Migrants is an exhibition of African-American farm worker photos I took in the 1960s curated by Michele Ellis Pracy at the Fresno Art Museum. The exhibition is now available for showing new venues.

While covering farm workers’ life, work, and union organizing in the 1960s I visited a number of African-American settlements in California’s San Joaquin Valley. These towns are a little known part of history, the results of the rural-to-rural stream of the Great Migration out of the Jim Crow south. more

Fresno Art Museum Director Michelle Ellis Pracy curated the exhibition.

Joel Pickford made the extraordinary prints.

Mark Arax and Michael Eissinger provided valuable background information on the history of the African-American settlements.

California Humanities Community Stories Program, Fresno Art Museum and its donors, and West of West Center for Narrative History of the Central Valley have provided funding.

Lloyd Tevis

once owned more land

than he could ride across

in a day’s time.

He fought Miller & Lux

for the water of the Kern River

way back before it became

a channel of dry sand.

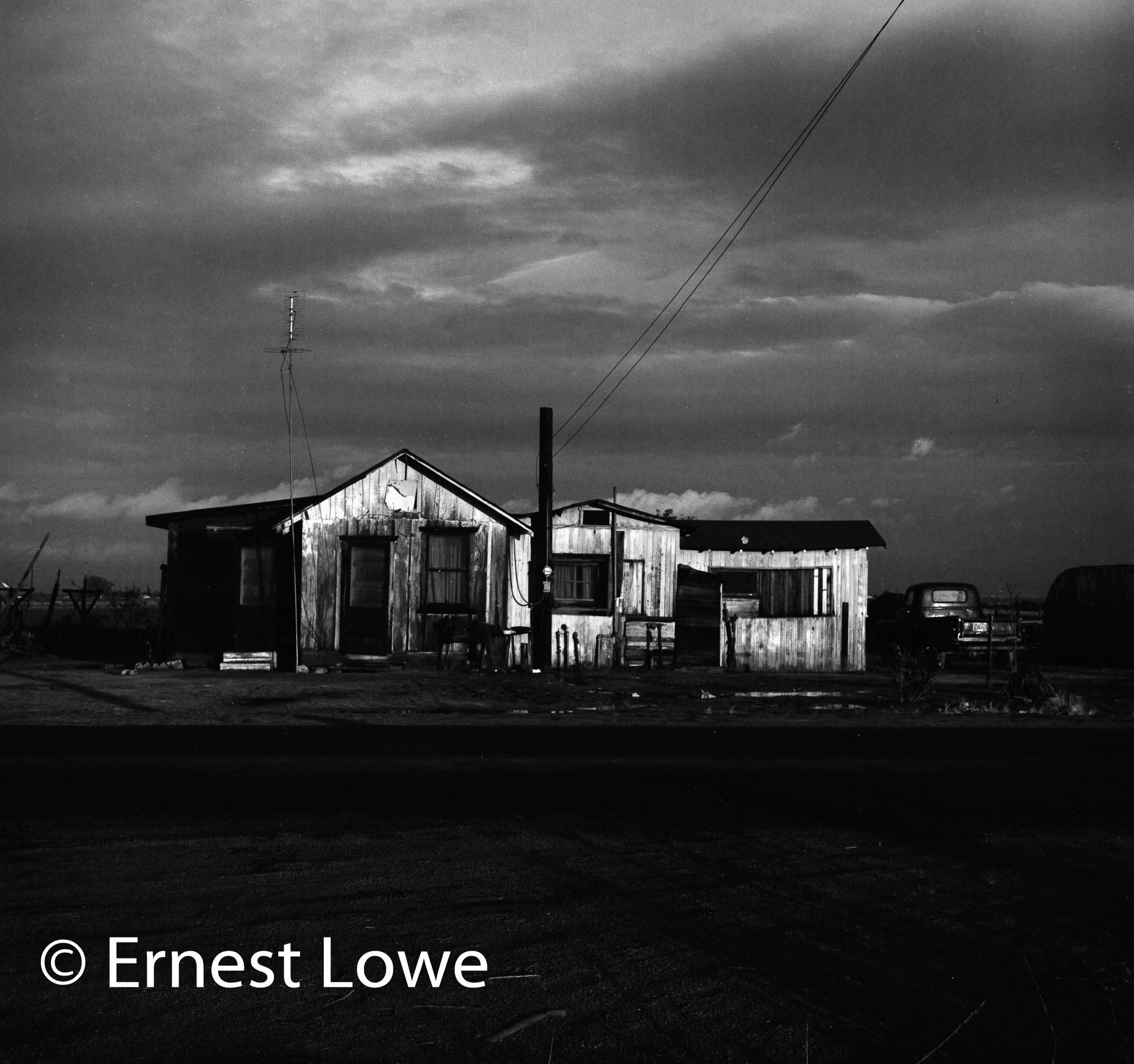

In 1961 I pulled off 99

into Teviston

as a storm ended

and the dark sky opened

to let the setting sun shine

upon the shacks of Black Okies.

Teviston was lit up

puddles reflecting day’s last light.

The homes

pieced together from scrap wood

glowed intensely.

How would Lloyd Tevis

have calculated the value

of this one and only memorial

to his great wealth?

[link-library settings=”1″]

[link-library settings=”1″]